A study that examined a total of 70,000 veterinary cases showed that 40% of the complications that occurred could be attributed to surgical procedures. Inexperienced veterinarians were not surprisingly overrepresented in the material, but surgical errors are also committed by experienced veterinarians. Who doesn’t make mistakes during their career? We are humans, not robots.

Some of the most common mistakes made by experienced vets are caused by so-called cognitive bias. Cognitive bias is a mental shortcut where we draw hasty conclusions on the basis of previous experiences we have made. The problem with this is that our conclusions are not always correct, and this increases the risk of misdiagnosis or wrong treatment.

The list of possible mistakes we can commit is almost inexhaustible, and I myself have made quite a few stupid mistakes during my career. In fact, there are two types of surgeons; those who have made mistakes and those who will make mistakes. Possibly there is a third type as well; those who have made mistakes but won’t admit it.

In this little article, I have listed mistakes that I believe are the worst we can commit, primarily because they can be avoided. This is not to say that these errors are statistically the ones to top the error list for veterinary surgeons, but I think they are important because they are relatively easy to do something about.

Here goes;

- Incorrect patient selection.

This one tops my list, and for good reason. Choosing the right patient for the right procedure is crucial for the patient to have a good outcome. A surgeon will never be better than his patient selection, and this is where we have the best opportunity to succeed. As a surgeon, you must always have carried out a cost/benefit assessment before subjecting an animal to surgery. Most people can learn the craft with time and effort, but knowing which patient needs surgery and which one would be best off letting nature sort things out is a fine-tuned skill. It requires good basic knowledge, but above all it requires a certain humility and, most of all, experience. If you don’t have the experience yourself, you can learn a lot from seeing practice with a good surgeon. And by that I don’t mean the surgeon who thinks that everything should be cut. - Not knowing your own limitations.

Our focus should be on the patient and to ensure that the patient will have the best possible outcome and opportunities for a long and pain-free life – our focus should not be on testing new methods or the excitement of surgery. If you have not performed the surgery before and do not possess the necessary experience, the patient has better options by being referred to a more qualified surgeon. There is no weakness in this – on the contrary, it is a strength to be able to see yourself from the outside, and also an opportunity to learn more. Ask if you can join the surgery when you refer! - Not reading medical records or looking at diagnostic imaging before surgery.

A rather obvious category, I know. But still, many of us have such busy everyday lives that this can sometimes be forgotten. It should never be forgotten! Because in the journal, if we put aside our cognitive bias, there may be important information that can make us see a case in a new light. Perhaps there is information there that changes our opinion about what is best for the patient? Perhaps you see something on the radiographs that the other vets have overlooked, and which makes you think differently? - Not acquiring basic knowledge and skills

It is incredibly boring to learn about instrument handling and suture materials and more fun to learn an exciting new surgical technique. I will be the first to admit that in my first years as a surgeon I just did “like the others”. If you had asked me about the characteristics of the various forcepses or suture materials, I would probably not have known. I wasn’t particularly strong at anatomy either after, as a student of anatomy, I found the smelly dog carcass extremely tedious. After seeing what wrong tissue handling, wrong choice of suture material ,and missed anatomy can lead to, I now know better. If I had to choose one singular tactic to become a better surgeon, I would definitely choose to learn “the basics” first. There are few fields where you can skip the basics and go straight into expert mode. The same applies to veterinary surgery. - “One size fits all”

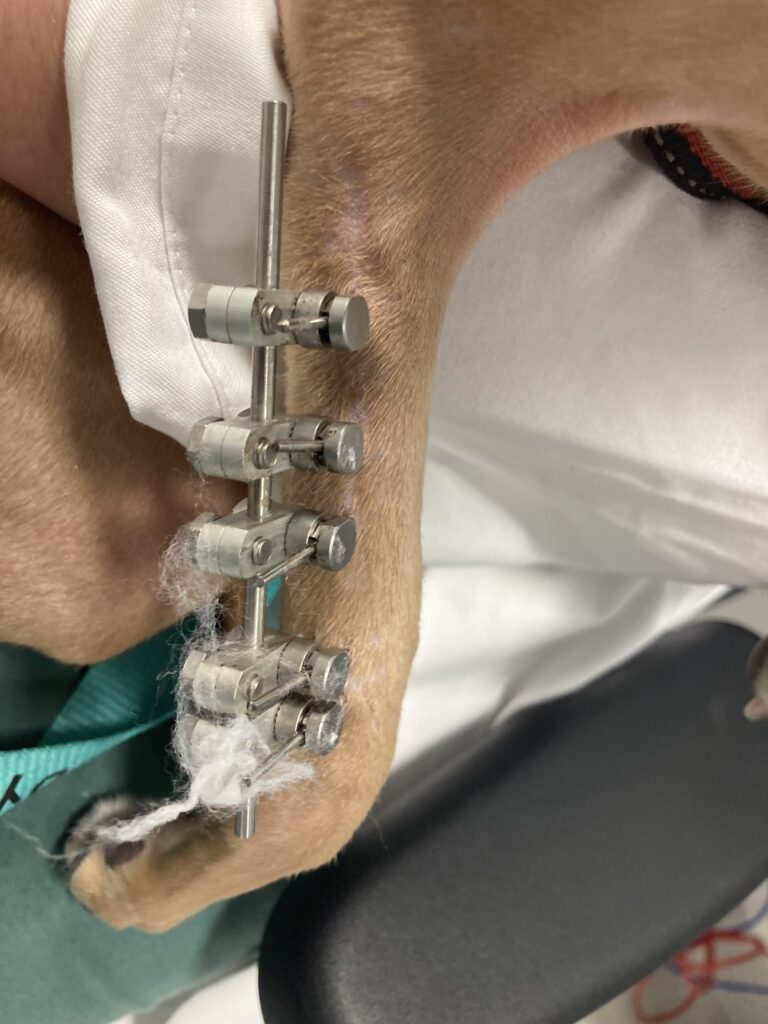

Admittedly, a good colleague of mine once said that “the more methods developed to correct one disease, the less likely that any of them will be particularly good”. There may be a lot of truth in that, because if we had one superior method, surely we would just continue with it? Nevertheless, there is no one surgical technique that can help everything. As veterinarians we have to familiarize ourselves with and learn so much, and it is not possible for us to become as specialized as human surgeons are. Therefore, it is sometimes convenient to just use the technique with which we have gained some experience and that we can perform without significant difficulty. For example, it is quick and easy to put a plate on a fracture, but sometimes we know, deep down, that an external fixator would have been better for this particular patient or this fracture. Don’t be tempted to do what is easiest for you. Use your knowledge and choose what is best for the patient, even if that means referral. In the long run, it’s more rewarding too! - Believing that antibiotics will save you from bad choices.

Much of this goes back to point number 4; poor basic knowledge inevitably leads to more complications. Some of the most important things in this respect are asepsis, tissue handling, choice of suture material, and time expenditure. If you are sloppy with your preparations, heavy-handed with the tissues, choose the wrong suture materials, or are poorly prepared so that the minutes fly by, antibiotics will not save you. It is better for the patient (and humanity in general) that you spend some time increasing your level of knowledge, than spending precious and unnecessary antibiotics. - Poor planning.

Everything is connected, and lack of planning can have many unfortunate consequences. First, it can be difficult to be creative when you’re facing a surgical wound, perhaps with a surgical team waiting for you, anatomy you don’t recognize, and a bleeding you didn’t anticipate. Secondly, it can be difficult to come up with a decent alternative if you have not already read or heard about the procedure. This, in turn, will cause you to make hasty and often bad choices in the operating theatre, which in turn increases the risk of unnecessary time spent, as well as complications. I would never enter an operating theatre without having familiarized myself with the problem, taken my measurements, or refreshed my knowledge of anatomy if necessary. I don’t set foot there until I’ve made a plan A, B or C either. Far too many times I have experienced that plan A and B did not work and that I had to invent a solution off the top of my head. It is unnecessary and increases the risk of complications that could have been avoided. - Not following the patient postoperatively

This does not necessarily apply to all patients, but it definitely applies to patients with orthopaedic or neurological disease. Many owners follow the instructions you have given with millimeter precision and have a low threshold for getting in touch if something deviates. Unfortunately, other owners do not, and this is a factor of uncertainty that we cannot ignore in our profession. A fracture can heal quickly. Unfortunately, this also applies if it has come out of position or if the implant has failed. Some owners are unable to judge whether the dog is better. We should not completely rule out the strange placebo effect that payment for expensive surgery has on the perception of the animal’s recovery. So how do we avoid having to clean up after catastrophic complications that could have been discovered weeks before and are therefore now virtually impossible to treat sensibly? We take the patient in for regular check-ups. Not always to do something, not always to take radiographs. But to check that the patient is well and that things are going in the right direction, so that we can intervene before it is too late. - Not counting gauze swabs before closing body cavities

“I don’t need to count gauze swabs because I never leave any in the abdomen.” Famous Last Words! So-called gossypibomas (forgotten swabs) make up an estimated 0.2 per cent of all laparotomies in dogs, and in a worst case scenario can end with death as they tend to attach to organs. Several of these swabs have probably been left there by vets with the above attitude. Our job is unpredictable, and if you have received 25 swabs and are suddenly faced with life-threatening haemorrhage, I think you are giving yourself more confidence than is warranted if you think you have full control over them.

There’s a reason pilots have checklists. That’s because they work and because they reduce the incidence of serious errors. Make a small checklist – at least make it a routine to count gauze swabs. Without exception. - Not learning from your mistakes.

This applies to more fields than ours. If you get cats back with their intestines out after ovariohysterectomy, they won’t stop coming back if you continue doing the same things. Look at your routines, not least the choice of suture material. If you always get patients back with seromas in the surgical wound, consider your basic surgical technique. We hate having to admit it, both to ourselves and to others, but the root of complications often – but not always – lies with ourselves.

“Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it”

George Santayana, Spanish philosopher.