https://doi.org/10.1111/vsu.14061

A recent study from the Ralph Veterinary Referral centre in the United Kingdom looks at the possibility of treating intercondylar humeral fissures in ways other than inserting a transcondylar screw, specifically omitting the screw and instead performing a proximal osteotomy of the ulna.

The background is the well-known disorder humeral intracondylar fissure (HIF), by many called incomplete ossification of the humeral condyle (IOHC), which is a common cause of forelimb lameness in spaniel breeds in the UK and elsewhere in the world. In the past it was thought that the condition was due to failure of the ossification centre between the humeral condyles, but more recently some have challenged this hypothesis and claiming that the condition may instead be due to a stress fracture. This is partly because many of the dogs diagnosed are well into adulthood and that previously normal elbows have developed such fissures with time. There is also the possibility that these are actually two different diseases; failure of ossification in younger dogs, and stress fracture in adult ones.

A recent study found a cartilaginous lesion on the caudal humerus as a result of humero-anconeal incongruency. The authors of that particular study believed that this, in turn, was the cause of abnormal loading on the humeral condyle and resulted a stress fracture with time. If this theory is correct, the authors of the current study believe that one can heal the fissure just by adjusting said incongruity – for example with a bioblique dynamic proximal ulna osteotomy (BODPUO) instead of using the more traditional method; placing a transcondylar screw to compress or hold the fissure in place so it can heal.

The hypothesis in the study was that the osteotomy will result in the anconeal process moving in a more cranioproximal direction and thus avoiding the cyclic loading which, according to the authors, can cause a stress fracture of the condyle – and that this in turn will induce healing of the condyle without having to insert a screw.

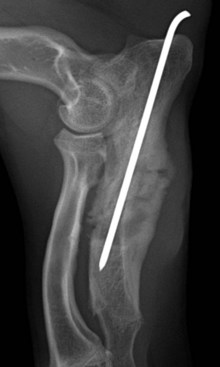

The authors collected 51 elbows, all from spaniel breeds, with intracondylar fissures, and chose to perform BODPUO which they then packed with human bone morphogenic protein (rhBMP) over a collagen matrix and stabilized with a thin intramedullary pin. On CT, they performed standardized measurements of the ulna preoperatively and after six weeks to see whether the proximal fragment moved proximally and cranially as desired. Furthermore, the bone density in the humeral condyle was assessed on CT before and six weeks after surgery, and a subjective assessment of pain was performed, while healing of the fissure was scored and complications recorded.

The results showed that 94 per cent of the dogs were pain-free upon extension of the elbow after six weeks, and those that still displayed pain were those which had been diagnosed with cartilage injury during arthroscopy. Almost 55% of the condyles were healed at this time, while 25.4 and 13.7 percent were in the process of healing or not healing, respectively.

Close to six percent had what the authors termed “minor complications”, where the intramedullary pin either broke or migrated. 5 dogs had “major complications” which affected healing either of the fissure or of the ulna osteotomy. Two dogs ended up fracturing the humeral condyle, while a third dog had persistent lameness.

In addition to this, the measurements showed that the proximal ulnar fragment had actually moved both proximally and cranially, as assumed in the hypothesis. The authors believe this technique may be a better solution than transcondylar screws since they believe the latter are associated with a number of complications, most notably seromas and surgical site infections. This argument is, in their opinion, supported by previously published results, where the complications with transcondylar screw vary from 15 to 69%.

Personally, I have seen few problems with these screws, which can be down to many reasons – such as the fact that I place them with a minimal incision or percutaneously under fluoroscopy, or that I live in a country with a low bacterial resistance profile.

You should also bear in mind that BODPUO is not a procedure to be taken lightly. It is associated with pain for the animal and is neither risk nor complication free. The dogs in the study were also cage-rested and confined to one room for 6 + 6 weeks, which I think most owners would find very demanding, especially for a young and active dog.

The current study has a number of limitations. It is a retrospective study based on already existing data. It is therefore not prospectively designed to give us answers to the questions asked. This is an inherent weakness, and the authors also discuss other weak aspects with the study; such as the fact that second look arthroscopy was not performed and the degree of joint incongruity therefore remains unknown. Furthermore, the study has no control group, the study population is small, and there are no objective assessment criteria for the clinical outcome – among other things.

What I think? I think the concept is interesting. Since I personally experience few problems with the transcondylar screws, mind you if they are correctly placed, and I am also careful about performing BODPUO if it is not the only (or best) way, I will probably not change strategy based on this retrospective study. Should the authors, on the other hand, be able to provide evidence that BODPUO is in fact better through a future prospective, randomized clinical study – then I would definitely be willing to change my opinion and strategy. Until then, I think it is useful to know about the technique as a possible “rescue procedure” for those patients in which a transcondylar screw for some reason has not worked optimally or where the screw has to be removed due to complications.

What do you think? Will you start performing BODPUOs on these animals?